Disability Visibility Called Out My Ableism

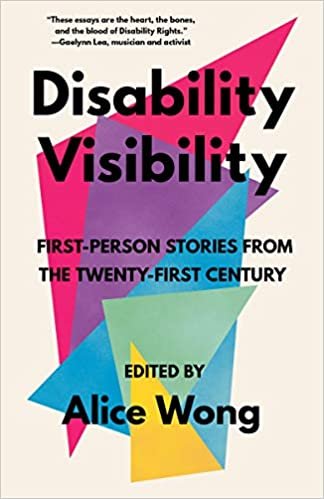

I first came across Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, as a recommendation from two educators who presented at the virtual Leading Equity conference in 2021. I wish I could remember who the presenters were, because it has significantly shifted my thinking about disability, especially in school spaces.

In particular, I am grateful for the chorus of first-person narratives in the book that, while diverse and even contradictory at times, helped to call out the layers of ableism in me that I learned from growing up in an ableist society as an able-bodied person. I have a lot of work that still needs to be done, but here I’ll share a few ways I’ve seen my ableism for what it is because of this book. (All the quotes included in the post are from Disability Visibility.)

While I’m likely not to say the statements below aloud, they certainly have crossed my mind when I have crossed paths with a stranger with a visible physical disability:

Harriet McBryde Johnson, for example, writes: “Strangers on the street are moved to comment:

‘I admire you for being out; most people would give up.’...

‘You don’t let the pain hold you back, do you?’”

Or Elsa Sjunneson’s similar call-out: “... the things able-bodied people say to disabled people, when they’ve never met us before, like the woman who told me that I was so AMAZING and BRAVE for ordering my coffee by myself.”

I very much appreciate Harriet McBryde Johnson response to these (now obviously) patronizing and ableist comments: “I used to try to explain that in fact I enjoy my life, that it’s a great sensual pleasure to zoom by power chair on these delicious muggy streets, that I have no more reason to kill myself than most people. But it gets tedious.”

Pity without understanding is dehumanizing, and even continues to replicate the power structures that are in place.

Additionally, the following quotes helped call out a number of layers in my ableism:

“Whether in East Asia or the United States, cultural values validate the narrative of worthy versus unworthy bodies. But the entire discussion needs to be rewritten as marginalized creators and activists repeatedly point out that there are no unworthy bodies. This lodges an innate discomfort into the very core of cultural norms that are shared by both continents… Taking up space as a disabled person is always revolutionary.” - Sandy Ho

Ho’s naming the narrative of worthy vs. unworthy bodies is something I didn’t have “eyes to see” before. But after this naming, it feels so obvious in the kinds of bodies we celebrate, we worship, and we are trained to work towards from childhood. Instead, I want to actively find ways to see all bodies as worthy and also work towards shifting cultural norms that create a hierarchy of body worthiness.

“Are we ‘worse off’? I don’t think so. Not in any meaningful sense. These are too many variables. For those of us with congenital conditions, disability shapes all we are. Those disabled later in life adapt. We take constraints that no one would choose and build rich and satisfying lives within them. We enjoy pleasures other people enjoy and pleasures particularly our own. We have something the world needs.” - Harriet McBryde Johnson

This called me out for thinking of some disabled people as “worse off.” I think my intention was out of compassion or pity, but it is a huge assumption to make of people I don’t know.

“Embracing my own joy now means that I didn’t always. Hope is my favorite word, but I didn’t always have it. Unfortunately, we live in a society that assumes joy is impossible for disabled people, associating disability with only sadness and shame. So my joy–the joy of professional and personal wins, of pop culture and books, of expressing platonic love out loud–is revolutionary in a body like mine.” -Keah Brown

Again, I made so many assumptions! If I picture my life as a disabled person (which is problematic because of all the assumptions I’ve made), I do assume it would be less joyful because of the things I couldn’t do. But that’s such a limited (and ableist) view of disability and of joy.

I could add so many more quotes and voices that were instrumental in this text in helping me see the ableism in myself. There are so many other layers in this book that address the intersection of disability with race, gender, sexual orientation, culture and the climate crisis.

Living in ignorance is not neutral. It allows the ableist system to continue.

The problem, as we able-bodied people are often taught to see it, is not disability itself. The problem is ableism and a society that is structured in such a way that causes harm to disabled people.

While this book is not an “education” book, it is a must-read for educators at all levels.

This book is so much more than just a calling out of ableism to able-bodied people like myself. It’s a celebration, it’s mourning, and it’s an affirmation of life and humanity. But above all, I found this book to be love.

I’ll let the words Talila A. Lewis spoke in their eulogy of Ki’tay D. Davidson drive that point home:

“Solidarity for Ki’tay means active resistance to the status quo— letting all people know that they are respected, cherished, valued, and loved… May we ever uplift, share, and act out your truth: Love Wins.”